June 28, 2004

Chapters

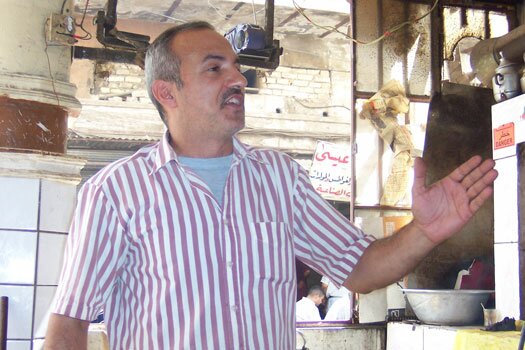

Abu Talat picks me up at my hotel and we’re off through the uncharacteristically empty streets of central Baghdad en route to the airport. It’s early enough that we drive with the windows down rather than running the air conditioner, and the warm breeze carries the sounds of shop owners sweeping the sidewalks in front of their stores, palm fronds rustling in the wind and growling treads of Bradley fighting vehicles as they rumble past.

Neither of us speaks much, as we said most of our goodbyes yesterday. When you spend three months with someone under the constant threat of a random death, you grow pretty attached to them. Greater than this, however, is the fact that this man I’ve worked with so closely as my interpreter/driver/fixer has become one of my best friends.

We’ve cried and laughed together, been shot at by US soldiers, interviewed mujahideen and exchanged knowing glances when members of various ministries have lied to us. Most of all, we’ve worked hard on reporting the situation on the ground in Iraq. “You are my brother, Dahr,” he has told me so many times. “I work with you because I know you are here to tell the truth.”

He could have taken better paying jobs with other news outlets. Like many of the other Iraqis who have chosen to work with me and my colleagues, he is extremely overqualified. Yet this work for him is his passion.

We pass US military patrols and helicopters as if the increase in their presence will somehow bring more security here as the temperatures rise by the day.

Three checkpoints later we arrive at the final drop-off area for the airport. See, Abu Talat is not allowed to go to the airport. His airport. I can, but even though he is Iraqi, he is not allowed to take his car past the final checkpoint.

“You can’t go further,” a gruff soldier says in a thick, southern accent to Abu Talat after glancing at my passport. “Pull the car over there and drop off Mr. Jamail.” We slowly pull onto the gravel and reluctantly get out of the car together.

“We will stay in touch,” Abut Talat says to me as we hug goodbye. “Insh’allah, we will stay in touch until you return. You are a friend of the Iraqi people.” I’m tongue tied and feel awkwardly full of emotions for my dear friend. “Take good care of yourself and your family, habibi. I’ll see you in September, insh’allah.”

I slowly walk up to the road to get into another car that will take me the rest of the way to the airport.

I look back and see Abu Talat standing by his car watching me, dedicated to the end. I wave and smile, as does he, before getting inside the car. I look out the back window and see him watching me drive away.

How does one reconcile being able to leave here? We all know it’s going to get so much worse; so much worse even than days where over 100 Iraqis are killed by car bombs, contractors kidnapped and beheaded, prison scandals, soldiers dying, infrastructure in shambles, and a new prime minister who is poised to become the next strong man of the “New Iraq.”

And I get to leave, while my dear friend must stay and do his best to get by day after day.

I am driven the rest of the way to the airport by two Iraqi Policemen. We drive by a huge row of concrete suicide barriers topped with razor wire -- the once finely landscaped area is brown with dead vegetation, strewn with garbage. “This used to be green and beautiful,” said the police captain as he drove, waving his hand across the area, “but now it is all dead.” After pausing he adds, “Our situation is like this now.”

All I can do is nod.

Pulling into the parking area we pass several mercenaries near the Baghdad Airport sign; one of them - a fat, pale younger western man wearing a red bandana over his head, poses with his small automatic weapon under the sign. He forms an awkwardly manufactured smile as his acquaintance holds a camera.

Inside the airport there are large crowds of people waiting to get out. Royal Jordanian has added an extra flight -- there are three today, all of them fully booked. Folks aren’t sticking around for the “celebrations” of the “handover.”

After a while I board the NGO Air-serve plane, and after a short ways to the runway I am pressed back in my seat as the engines of the 14 seat turbo-prop whine with power. We race down the runway for a quick take-off which then has us buzzing along just 20 meters above the runway to gain speed.

Just as we approach the end of the runway my gut slides back to my lower spine as the plane promptly jerks upwards into what feels like a 50 degree climb, shortly thereafter banking hard to the right. We climb in a corkscrew up to where war-torn, occupation-riddled Baghdad below takes on the appearance of the sprawling, proud capital it once was. The green waters surrounding Saddam Husseins’ old palace near the airport sparkle in the sun.

Once the altitude is attained which has us out of the range of rockets, we finally straighten out and head towards Jordan. After Baghdad fades out of sight, I drift into a deep sleep. Later I read that a transport plane which departed Baghdad 6 hours after mine was shot with small arms fire, killing one of the passengers. Nevertheless, flying remains safer than driving out of Iraq.

The culture shock is already apparent in Jordan -- cars drive within the lanes, there are no military vehicles rolling through the streets with their guns pointed at everyone, no worries about roadside bombs, no morning mortars at the CPA, constant electricity at the hotel where I stay... the differences are ubiquitous.

The next day I watch the news of the US-led coalition granting full “sovereignty” to the US-appointed Iraqi Interim Government two days earlier than everyone expected in an effort to avoid the large-scale attacks that are assured for June 30th. I note how the insurgency is now referenced by mainstream media as an entity to be dealt with. Indeed, as they’ve effectively derailed the previously laid plans of the occupation forces to “handover” power to the new government.

Of note as well is that Prime Minister Allawi has said that his first move will be to take actions to insure the security of the Iraqi people by looking into imposing some form of martial law.

Not only are the occupation forces and new Interim Government of Iraq inhabiting the old palaces and military bases of Saddam Hussein, they are now fully engaged in threats and heavy handed tactics reminiscent of the old regime, that the Iraqi people know all too well.

June 25, 2004

Where Children Laugh at Bombs

How much worse does it need to get here before the occupiers consider changing their policy? One hundred dead every day? In light of what happened here yesterday, it appears as though we’re heading in that direction. For those of you who think June 30th will signify a decrease in the number and magnitude of attacks against the occupation forces after the “transfer of sovereignty” -- think again.

After having coffee and listening to the Coalition Provisional Authority's "Green Zone" receive its morning mortars, I was out the door to get some things done, as my time here is drawing to a close. After over 11 weeks back in Iraq, I’ve never been as exhausted as I am now.

Baghdad seems ever closer to lockdown today. I took a cab over to the Palestine Hotel -- a small “Green Zone” where so many corporate journalists and mercenaries live behind suicide walls, razor wire, and soft checkpoints. It closely resembles another mini-“green zone” over at the Al-Hamra and Al-Dulaymi hotels, where journalists and mercenaries are hunkered down behind concrete suicide barriers and checkpoints.

En route to the Palestine to run an errand, there were Iraqi Police and Iraq Civil Defense Corps on nearly every street corner. My cabbie pointed to them and laughed while shaking his head. “La, la Amerikia,” he says (No, no America). The absurdity of it all increases daily -- so many of the ICDC wear face masks. Not that I blame them, for if their identities were known by the mujahideen, they and/or their families would be dead. Not a good time to have any affiliation with the occupiers -- consider yesterday's attacks as a case in point.

There certainly weren’t any inside Baquba yesterday, where I was faced with another great irony. During all of my five months in Iraq from my two trips here, the only two times I’ve been shot at have both been by US troops. Yesterday was yet another example of this, when our car was shot at five times by troops in a Bradley which sat in a nearby palm field as we passed.

Warning shots, for sure, or I wouldn’t be typing this right now. But the adrenaline flows about the same when bullets are whizzing near the car. This occurred while we watched two Apaches engaged in strafing part of the city, bobbing above the date palms in dive bomb-like flight patterns, then swooping back out of sight as they trailed smoke behind their blazing guns.

The city was a ghost town. Inside it reminded me of Fallujah when I was there in April. The main roads sealed by the military, and the constant buzzing of unmanned military drones telling the residents that more air strikes were simply a matter of time. Just like Fallujah.

All the shops were closed, bits of plastic bags and garbage were blown about on the streets by a dry, hot wind. Torn Iraqi flags fluttered in the winds, dogs running here and there.

We had lunch in Baquba with a Sheikh I have become friends with. Just before lunch, several loud bombs exploded nearby. My friend Christian Parenti and I looked at each other with wide eyes while the Sheikh, his brother, Abu Talat, and an older man with us who is a Haji began to laugh. “This is normal, even my children laugh at the bombs now,” said the Sheikh.

In the next room the children were laughing excitedly.

The Sheikh remained calm throughout the blasts. He smiled and told me: “God will take us when it is time. People are killed in their homes by warplanes, yes. But people in the middle of fighting remain unharmed. It is up to God. We are a people of faith.”

While these people were in no way connected to the resistance, their anger towards the occupiers seemed to fuel their acceptance of the mujahideen in their city.

“The mujahideen are fighting for their country against the Americans,” said the Haji. “This resistance is acceptable to us.”

His opinion is reflective of those held by more and more Iraqis I talk with nowadays.

When we were exiting the embattled city, we drove slowly past a bullet-riddled car on the median of the main road. It appeared as though the car was trying to turn around. The drivers’ body lay in the middle of the road, feet the only parts uncovered by a black mourning flag draped over his corpse.

Fifty meters further down the road there were patches of pavement mangled by tank tracks. Near these sat a large pile of empty machine gun shells, glistening gold in the hot sun.

The scene had all the classic signs of an Iraqi seeing a checkpoint and attempting to turn around quickly... which appears to have led to yet another indiscriminate killing of a civilian.

A bit shaken by this, we continued on and saw several Humvees and soldiers blocking our exit further down the road. We pulled the car over, and while Abu Talat waited, Christian and I walked the quarter mile towards the soldiers.

“We are unarmed journalists,” we took turns yelling while holding our press credentials in the air. “Please do not shoot! We just want to leave the city!”

The walk felt like it took 4 hours... halfway there I noted three soldiers who knelt down and kept us in the sights of their guns. I looked behind us to see a string of cars in a wedding party approaching. The timing could not have been worse.

I walked towards the side of the road, but Christian wisely suggested we stay in the middle and keep walking. Our pace quickened, our shouts grew louder and thankfully the wedding party turned around.

Needless to say, the soldiers are a little touchy about cars that approach them these days, as Iraq has averaged more than a suicide car bomb per day this month.

The soldiers understood our situation when we approached them and asked to be allowed to leave. Christian went back to get Abu Talat and bring the car up.

I spoke with a Sergeant, and said, “After seeing that bullet riddled car and the corpse back there, we thought it’d be better to approach you guys on foot.” He told me that the car had rammed a tank, so they had to shoot it. “Crazy mother-fucker, that guy was,” he added.

Since I recalled that, aside from being completely riddled with bullets, the car was intact -- particularly the front end of it -- I kept my mouth shut.

Two photographers were there with the soldiers. They were very scared, and one of them asked me, “Did you see any bad guys in there?”

I said, “I did not see any mujahideen inside the city.”

I wondered why they, like so many other journalists here, won’t venture out amongst Iraqis to report on how the occupation is affecting them. Of course it’s dangerous, but then, why else are we here?

June 24, 2004

Ask Dahr: 7 Questions and Answers with Dahr Jamail

The other night, I sent Dahr Jamail a batch of seven questions, culled from the first several dozen emails his readers sent in response to my recent appeal for letters. I sent the originals along as well. Dahr is reading them all and doing his best to reply to those which requested a response.

Here is the first set of questions and answers...

Q: It seems obvious that at least some of the "mujahideen" are causing as much damage to Iraq as they are to the occupiers; maybe more. I desperately want to be able to support some group or movement in Iraq. Am I missing something, or is no one -- including the resistance -- worth rooting for?

Referring to the mujahideen as one group is a misnomer. They are comprised of numerous factions, many of which loathe one another. Their bombs (IEDs) continue to kill Iraqi civilians on a regular basis... yet, overall, they are responsible for far fewer civilian deaths than the US military, which has killed at the very least 10,000, including the invasion and occupation.

If you want to support a group in Iraq, I suggest the Red Crescent Society or Doctors without Borders -- they both do very good work here for the Iraqi people. I suggest avoiding any group affiliated with the occupation (CPA). Any funding or supplies you donate will only be guaranteed to reach Iraqis directly and timely if you go through the aforementioned aid agencies. In addition, that way you would help keep the corruption here (which is rampant) to a minimum.

Q: Is there much bribery or black market trade in day-to-day life; and if so, how is it affecting people? Has it increased or decreased since Saddam Hussein left power?

Bribery has decreased since Saddam has been removed because there is less paperwork and bureaucratic interference for people needing help, and needing paperwork for identification. However, this is on the rise again as the US has encouraged the Ministries to build effective walls inhibiting access to various officials.

As far the black market, it is alive and well. This has increased very much. And without it, people would suffer even more. For instance, many medications are only available on the black market. Oftentimes, patients at hospitals are asked by doctors to go get the medications/supplies they need from the black market in order to get proper care, for the hospitals are unable to obtain what they need from the Ministry of Health.

Also, if it weren't for black market fuel, those who can afford to purchase it would be forced to wait 4-6 hours in petrol lines.

Q: How are Iraqis reacting to the recent U.S. missile strike in Fallujah? Was there a noticable surge in anger, or has the violence become so constant that it's anger is jus always high, always at a peak?

Most are enraged. There has been an extremely noticeable surge in anger, on top of the already high level of violence here. Most Iraqis do not believe that Zarqawi or his group are in Fallujah, and believe the strike was retribution for the people of Fallujah effectively ejecting the US military from the city in April/May. Most Iraqis I've spoken with about it believe it is yet another war crime committed by the occupiers.

Q: My question regards your ability to witness such suffering and death and yet maintain psychological balance. I am certain I would be unable to tolerate for 12 hours the conditions you witness and experiences for months on end. How do you manage?

Honestly, I have allowed myself to become a workaholic. Intentionally not giving myself too much time to think about the atrocities and suffering, because any time I do I find myself getting very depressed, very fast. However, I do take time to read books, and laughing at the insanity of it all with other westerners at my hotel helps to decompress. It is inescapable here though... for even holing up in the hotel for a rest day I hear the bombs and gunfire, and friends call with bad news on a regular basis.

Q: Your work is a lifeline for many of us, but I cannot understand how someone comes to the conclusion that providing information to others is worth the risks it seems you take, which seem far greater than those being taken by most other journalists. Why are you willing to put your life on the line doing the reporting that you are doing?

Thank you for the kudos. The risks I take are nothing more than those Iraqis face in going about their daily lives. I believe that witnessing and documenting the horrendous nature of this brutal occupation is necessary. I believe the reason the US and British governments are getting away with war crimes and the looting of Iraq is due to the lack of information being provided to people back in those countries. I believe if most people came here and witnessed what I have, they would do the same thing.

Q: I am desperate to believe that the Iraqis do not hate us, Americans, as people. Do the Iraqi people know that there is a huge percentage of Americans who oppose the war, and always did? Do they know that many of us work tirelessly to end the occupation and the ravaging of their country?

Most Iraqis I speak with are quick to differentiate between the US government and the citizens of the US. I make it a point to tell Iraqis, those who do express anti-American sentiment, that there are millions of Americans who opposed the invasion, and oppose the occupation, and are working very hard to help this situation.

Most Iraqis blame the US government, not the people of the US. They are quick to point out that they remember the worldwide demonstrations against the invasion, as well as that they believe Mr. Bush was never elected president; thus, the idea of true democracy existing in the US has been usurped by a small group.

Q: To what extent is Iraq being "re-Baathified", so to speak? We see the managerial class, the civil service sector and police chiefs, army chiefs, former Mokhabarat (secret police) people in key positions. How is this affecting ordinary people's hopes for a new Iraq?

It is being 're-Baathified' on many levels -- the Iraqi Civil Defense Corps, Iraqi Police, army, government posts, and many positions in the ministries. Mixed feelings on this - the response depends on who I talk with. But overall, most Iraqis are so desperate for security and a return of some type of basic infrastructure that they are willing to allow this re-Baathification.

I must point out that most Iraqis were considered Baathists before the invasion, due to that fact that in order to obtain a decent job, you had to claim yourself as a member of the Baath Party. So many of these who are being allowed back into their posts were never 'active' Baath Party members to begin with.

June 23, 2004

Penalty of Force

Mohammed works at our hotel. He just came up to deliver our laundry. When we asked how he was doing, he took off his sunglasses to show us a black eye. “Not so good,” he said.

Someone was drinking beer outside the hotel last night, and when Mohammed asked him to please move away from the entrance of the hotel the man stood up and promptly assaulted him.

“He said, 'This is the freedom, and I want to drink here,'” Mohammed recounted. “Then he beat on me some more.”

Mohammed used to work as a translator at Abu Ghraib. He quit because some mujahideen saw him coming out of the prison one day, pulled him out of his car, threw him on the ground, and while holding a gun on him said, “We will kill you if you complete your job with the Americans!”

Needless to say, he quit. Just 3 days before he was threatened, the mujahideen killed one of his friends from work. He knows of five other translators whom the mujahideen have killed as well.

After his death threat, he approached an MP at the prison and told him he was threatened by the mujahideen and could tell the Americans where his attackers went. He had seen them drive to a nearby home.

“That is not our job,” was the reply of the soldier when given the evidently “inactionable” intelligence regarding the precise location of resistance fighters who had assaulted an Iraqi employee.

While working inside Abu Ghraib one day, Mohammed saw a friend of his who had been detained. He knew his friend was innocent. Soldiers had arrested him when they raided his home and found 5 million Iraqi Dinar ($3500), which he had because he was about to get married. The soldiers suspected him of funding the resistance.

Yet Mohammed couldn’t speak to his friend. You see, he had once before made the mistake of talking to a friend in the prison. The punishment for that misdeed had been prompt: the MPs had locked up Mohammed himself after he had worked 3 months as their translator.

“During the morning I was working for the coalition as a translator,” Mohammed explained, “and that night I was a prisoner!”

He was held for 4 months before being released, at which time he was told by a soldier, “Sorry, you are innocent.”

But work is nearly impossible to find in Baghdad, so Mohammed resumed his work as a translator for another month. This time, he knew he knew better than to speak to an incarcerated friend. Nevertheless, he told MPs that his friend was not guilty of anything, and an MP told him, “We know he is innocent.”

Then came the incident with the mujahideen, and Mohammed had finally had enough.

Mohammed studied for 7 years to be a doctor, and even worked two years in a hospital. "I am a peaceful man, I've never fought anyone in my life," he explained. "But problems keep finding me here."

As it turns out, Mohammed was also detained by Baathists during the regime of Saddam Hussein. They held and tortured him for 6 months. Thus, his willingness to work with the coalition...

Yet another tragic story in occupied Iraq. One of countless tragedies that are woven throughout Iraq today. These days, I don't have to send a fixer out to find a fascinating story for me to cover. I can just talk to the man who happens to deliver our laundry.

Despite having the most powerful military on earth roaming the streets of Baghdad, the security situation continues to degrade from horrible to staggering. While every day in the news we see the car bombs and attacks on US soldiers, Mohammed’s incident last night is indicative of the general lawlessness which has engulfed the capital city under the occupation.

Crime is rampant, and looters abound. Not on the large scale as during the fall of Baghdad, but they are at work daily. For example, the other day at the site of a bombing, a car which was destroyed by the blast was pushed off to the side of the road. Looters promptly commenced stripping it of parts. Security guards and Iraqi Police stood by watching as men worked feverishly removing the tires.

Ominous signs erected by the Coalition Forces are scattered about Baghdad. Signs which ever so subtly warn people not to park in the wrong place:

Anyone Parking In This Area Will Be Detained

Signs at checkpoints which read:

No Photography, Violators Will Be Shot

And…

Use of Deadly Force Authorized

Stenciled warnings on metal sheeting that lines one side of a bridge over the Tigris River read:

By Order of The Coalition Forces

Do Not Tamper or Remove Sheets

Under Penalty of Force

“This is the freedom,” indeed.

June 22, 2004

Struggling To Survive

I revisited Chuwader General Hospital in Sadr City yesterday. Unlike at Yarmouk Hospital, the manager at Chuwader was very open about the desperate plight facing his hospital, where 78 doctors work with desperate medicine and equipment shortages to serve an average of 3,000 daily visitors.

I was taken on a tour where I saw the kitchen facilities in complete disrepair, toilets which overflowed across the floor in the intensive care wing, X-Ray equipment dated from the 1970s and beds lined up with patients in one of the dirty lobbies.

It was clear that not only does this hospital need immediate rehabilitation and re-supplying, but an entirely new hospital is required in the impoverished Sadr City to even begin to meet the needs of the 1.2 million desperate residents of this sprawling area, which experiences fighting between the Mehdi Army and the occupation forces on a near daily basis.

This is a hospital that can spend only $200 per day to feed its 308 in-patients. This is a hospital that is regularly invaded by US troops who, according to several of the doctors, walk straight into wards looking for fighters without consulting the doctors first.

Also here, an Iraqi subcontractor visited (and billed) to “repair” a malfunctioning X-Ray machine 6 times in a 30 day period last July/August. The machine remains in disrepair today.

As the tour continued, I had a gut level reaction of just needing to leave. I told Abu Talat: “This is enough. I have seen enough. We can go now.”

He put his hand on my shoulder and gently said: “We’re almost finished. I know you are tired, but let’s finish this.”

We were taken to see premature babies, kept two per incubator in a small maternity ward where fatigued nurses constantly monitored their fragile condition. My friend Tarek and I were allowed inside the room to see the babies -- their tiny bodies breathing rapidly while they struggled to survive.

Shortly after this we shook hands with Dr. Khaim Jabbar for and thanked him for showing us around, and walked out into the blazing heat and filth of Sadr City. After stepping over streams of raw sewage running under the stalls of the food vendors outside we got into the car and slowly made our way out of the slum that so many Baghdad residents call home.

I looked out the window at the grimy children playing in the garbage on which goats were feeding and considered that if those premature babies did, by chance, survive -- this would most likely be their life.

Tears welled up as I felt a deep despair. “My God what can be done about this? What is the point of all this work when nothing seems to be changing here?” I asked, more to the people I gazed upon, rather than to Tarek or Abu Talat. They were both quick to reassure me that we can’t stop this work we do, that it is worthy and needed while I wiped my tears.

Abu Talat softly said, “I think it is because you know you are leaving soon also.” He knows me better than I know myself sometimes. And he was right.

Later that evening, with yet another instance of perfect timing, my editor forwarded me a long list of comments from various readers who expressed support for the reporting I’ve been doing here for 11 weeks now. I want to thank you very much for taking the time to write these. Those comments have never failed to arrive at the perfect time when I’ve needed the support most.

It is easy to get tunnel vision here -- focusing day after day on the dire situation this occupation has created in Iraq. Easy to forget that people are actually reading about the stories, and are working hard in several countries for change. Change that Iraqis need so desperately.

Exporting Violence

The evening of the 21st found me at a CPA-approved demonstration of Shia men in support of the recent US airstrike of Fallujah. Remember, demonstrations in Iraq now must obtain permission from the CPA, otherwise risk being broken up by the military which has so often led to casualties of unarmed demonstrators during the occupation.

These CPA-sponsored demonstrations also tend to have US helicopters providing air support for them, which tends to be a giveaway as well.

The demonstration wasn’t in support of killing the people of Fallujah, only those responsible for the killing of 7 Shi’ite truck drivers there a short time ago. Several of the men were quick to point out that they believed most of the people in Fallujah were honest and good. One of the fathers of several of the slain men showed us gruesome photos of their mangled bodies while three large mortar blasts rocked the nearby so-called “Green Zone.” The concussion of the blasts reverberated in my bones, but the conversation continued uninterrupted.

This is Baghdad today. This is normal.

Hakkim had spoken there, and several of his Badr “organization” were present -- complete with full military fatigues and combat boots, submachine guns, sniper rifles, and AK-47s. (The quotation marks above are because the Badr Brigade was renamed when it “disbanded,” to the “Badr organization.”) This despite the statement that Al-Hakkim’s militia had disbanded, and his guards were only supposed to be carrying “light weapons.” Iraqi Police drove slowly by while nervously watching the members of the heavily armed Badr “organization” from their trucks.

Meanwhile, Iraqi anger seethed about the second air strike in Fallujah in 4 days, which Iraqi Police and residents of Fallujah are claiming killed nobody but civilians. Yesterday, the bodies of 4 US soldiers were found in Ramadi, which isn’t a surprise. During each of my recent visits to Ramadi, I’ve found the people there in total solidarity with Fallujah. Most of the tribes there occupy both cities, and many people in Ramadi even refer to Fallujah as part of Ramadi.

Ramadi and Baqubah both remain tense with recent fighting; the potential of them turning into the next Fallujah remains quite present.

During a recent visit to pick up my airplane ticket out of Baghdad, I learned that the airport road and all civilian flights out of the capital will be closed on June 30th. The service I’m using was instructed to rebook all of its June 30 flights to the 29th or July 1st. It will be interesting to see if the airport is reopened on July 1st. The nickname for the airport road is “RPG Alley.”

This just underscores the tenuousness of the grip the US occupation forces have on the situation here. It certainly wouldn’t take much to tip this delicately balanced scale into complete chaos and bloodshed. The feeling amongst many Iraqis is that any semblance of control the “coalition” appears to have is merely an illusion.

I saw a clip on BBC of US troops handing out Frisbees to residents of a village near Fallujah. The clip began with a Marine saying, “What happened on 9/11 really affected me, so our duty now is to export violence to the 4 corners of the globe so that that doesn’t happen again.” And Iraq has which connection to 9/11, exactly?

Maybe the US could export aid to the hospitals of Iraq rather than Frisbees and violence?

Just a thought.

(Un)Covering Torture

On May 4, we published a story about Sadiq Zoman, an Iraqi who US troops abducted from his home in Kirkuk and, one month later, dropped off at a Tikrit hospital in a "persistent vegetative state," his body exhibiting telltale signs of torture. We told the story of Mr. Zoman’s family -- nine daughters and a wife who have sold every last possession to pay for his care as he lies unresponsive and helpless. They are desperate for answers and accountability from the foreign forces occupying their country, and who, from all evidence, deprived them of a husband and father as they knew him.

We know the Zomans’ story was compelling to many of our readers. Several of you wrote in to ask how you personally could donate to Sadiq Zoman’s family. We were moved by your generosity and your desire to see the Zoman family cared for after the tragedy that has been inflicted upon them, quite likely with money taken from you in the form of taxes. We heard your outrage, and we share it. Since then, the National Grassroots Peace Network has started a fund for donations to help the Zoman family (see below for more information).

Click here to read the rest of this important editorial.

June 20, 2004

“This is just like Afghanistan…”

The floor of my hotel rumbled as yet another bomb detonated in central Baghdad at 8:55 am today. My colleague down the hall showed up and asked, “Did you feel that?” I responded, “Yeah, Abu Talat is scheduled to show at 9 so we can go to work…get your stuff.”

As usual, Abu Talat was right on time and we were off into the heat and traffic, inching our way toward the blast sight near the Central Bank.

The usual crowd milled about a crumbled area of curb where the small bomb had turned a nearby iron gate into a tortured metal jungle-gym. Fragments of concrete lay strewn about the street as anxious security guards wearing black flack jackets nervously direct the traffic which creeps by.

“It is the Americans and Israelis who are planting these bombs,” said Hammad Hussan, who is a security guard at the nearby bank. His hysteria is not uncommon here in Baghdad, where a day without an IED or car bomb has become an oddity. The four Iraqis wounded by the blast had already been evacuated. Hammad and several of the other guards believe the attack is meant to destabilize the banking system, as it occurred at the time when money is usually deposited at the bank.

One of the cars which was ripped up from the blast sat nearby--looters already propping bricks under it whilst taking the wheels off under the supervision of bank security guards.

At a nearby tea stall the owner, Hussein Ali openly expressed his grievances toward the occupation. Being an ex-Iraqi Army Captain, he refuses to join the new army. “I don’t like the Defense Minister, and nobody knows who these people [the new government] are,” he said while sweat beads on his forehead. The mornings don’t start off too hot, but by 10 am it was already 90 degrees.

Another man sitting nearby as we drank tea jumped in, “There is no security here, and this is why we have no jobs.” He continued, “The Americans can never bring security here, everyday we have these bombs killing Iraqis, for what?” Despite so many people having grown weary of the fighting, bloodshed and bombs, Iraqis' anger toward the occupation is rising along with the stifling summer temperatures here.

I continued my ongoing hospital research after the lively tea discussion over at Yarmouk Hospital. The Assistant Manager, Dr. Hayder Al-Safar told me how there were no problems there, that if they ever have shortages of any medicines he calls the US-funded Ministry of Health and within days they are provided.

I stared at him blankly, while making it a point not to ask him the question in my mind which is, “So doctor, how much, exactly, do they pay you to lie?”

See, it was just weeks earlier that I’d visited Yarmouk Hospital.

At that time, Dr. Namin Rashid, the Chief Resident, stated that the only medical help his hospital had received lately had been a load of medical supplies from Grand Ayatollah Ali Al-Sistani.

He complained that the Ministry of Health consistently failed to give them enough supplies, and his hospital currently only had 100 sets of IVs and blood transfusion equipment. Yarmouk serves 5,000 patients each day.

He stated then, “We are getting less medical supplies now than we were during the sanctions!”

He said his hospital is receiving only one half as many supplies as it was prior to the invasion.

He stated, “The Ministry [of Health] talks a lot, but they do no action for us.” He said that people are getting injured or killed on their way to the hospital because of the dismal security situation. He said, “Bremer came here and talked a lot at the beginning of the occupation, but nothing has changed.”

His anger and frustration was palpable when he discussed how many gunshot victims he treated who are shot at US checkpoints, and said that he too was afraid to even leave his hospital.

He was outraged at the fact that his hospital treats 10-20 gunshot victims each day, whereas before the invasion they treated an average of one per week, sometimes only one per month.

But it had been a little while since Dr. Rashid had told me these things, so Abu Talat, my friend Tareq and I decided to go get a second opinion about what Dr. Al-Safar had just told us.

Abu Talat, who is like a guided missile when it comes to gathering information for my stories, insisted we go straight to the supply room of the hospital.

There we met Dr. Um Mohammed at her desk. She is responsible for assisting in running the supply distribution for the hospital. At first reluctant to talk with me about supply shortages, I let her know Dr. Al-Safar had told me everything was great.

“He says these things but he knows better,” she said while sitting very still, “We tell him what we need, and he says that he asks the Ministry of Health but they don’t give it to him, so why bother?”

She has grown weary of the broken promises from the coalition, scattered like useless debris over the wreckage of her shattered country.

“This is just like Afghanistan,” she said while beginning to open up more about things that she has obviously been internalizing, “We lack everything here.”

Her talk goes straight to those responsible for the lack of supplies--those funding and controlling the Ministry of Health: the US-led CPA.

“They’ve destroyed the foundations of Iraq. What do you think we can do with no foundations,” she asked, her eyes looking deeply into mine as I write furiously on my note pad while maintaining eye contact. “Even if the Americans stay here 15 years, there will be no security.”

Her dark eyes are like lasers as her focused discussion sears into one topic after another. She is on fire.

“The West knows what is happening here but nobody can stand up to the colonial superpower America. Look at this hospital! Anything they do or build is superficial, not fundamental,” she stated firmly, “Bush is a great actor while he speaks of freedom.”

She shifts to the prison scandal, “Abu Ghraib attacked the dignity of the Iraqi people. America didn’t become barbarians from killing Indians, Vietnamese, Central Americans, Afghanis, and bombing us and our young children who now have psychological scars?”

“I never liked Saddam, nor did I support him, but at least under the dictator there was order and some basic services,” she continued vehemently, her eyes becoming more intense after I’d thought that impossible. “Now there is no order, no electricity, no fundamental stability.”

Abu Talat suggested that she be careful, speaking so sternly about the failure of the occupation. She looked piercingly at him and says; “I am afraid, but not for myself. I’m not afraid to tell the truth, I’m only afraid for my family.”

Nevertheless, she continued with this chance to express her anger.

“So many Iraqis said the Americans would treat them better than Saddam, but when they saw the Americans stealing and killing, the Iraqis started to think differently about them.”

Though the topic is dancing about, the passion of her feelings links it all together. “The bad side of the Americans has been exposed to Iraqis now, and this is what we are seeing,” she said, referencing the indiscriminate street killings, Abu Ghraib and the wedding party massacre. “Me and my husband used to want to go to America,” she said before taking a long pause without looking away.

The next words are from her eyes, and she says, “Now….never.”

She tells us a story of a truck that was turning around near a US tank and was shot because it was too close. Everyone in it was severely injured, many had lost their eyes in the shrapnel. She was the doctor who wrote up the report, and had written, “occupying forces” for those responsible for destroying the truck. She said the administrator of Yarmouk Hospital crossed out “occupying,” then crossed out “forces” from the report.

“So the truck just exploded on its own?” she asked.

Several seconds were allowed to pass to drive home her point.

She then told of a car full of medications for the hospital that was traveling from the airport when it was shot by a passing tank, “And the tank did not even stop,” she added.

Her anger from being on the front lines, treating the casualties churned out on a daily basis by the occupation forces was palpable.

“Some Iraqis still believe the Americans are here to help them,” she said in disbelief.

“I pray that God shows them what the Americans are like,” she said unmoving, her eyes unwavering. “I pray that God sicks the Americans on them so they will see for themselves.”

She asked us if the occupation forces suffer from psychological problems, because she doesn’t think it is possible for anyone to do and say the things they do in Iraq and still be healthy.

She looked even deeper into my eyes and says, “Don’t imagine that the US has come here to do us any good.”

Abu Talat asked her who her husband is, wondering if her strong opinions have been influenced by him.

She looked directly at him and said, “These are MY thoughts and emotions! Who my husband might be is irrelevant to my beliefs."

We thank her and walk out of the hospital to find several Humvees out front, en route to what a security guard told us was yet another bombing.

Ask Dahr -- a Q & A

No weblog entry today, but we have a couple of exciting ideas in the works with regard to The NewStandard's Iraq coverage.

First, something we've been wanting to do for a while and can't wait on any longer: Dahr Jamail has expressed an interest in fielding brief queries from our readers about his work in Iraq, so we're going to give you an email address below to which you can send all those questions you've had rolling around your head about the situation in Iraq.

As his primary editor, I would like to add a request that people who appreciate Dahr's work send letters expressing that sentiment. Dahr has not made his email public previously in large part because he gets a significant amount of hate mail and death threats for telling the Iraqi people's side of the occupation story.

But Dahr does appreciate feedback from his readers -- including critical feedback -- so long as it does not include abusive language, personal attacks or threats. PLEASE feel free to direct any questions (or praise) you have for Dahr to this address:

Dahr will do his best to respond to all of the mail over the next few weeks, and some of the responses to questions posed to him will be published on his weblog and/or, in some form, on The NewStandard website. Dahr will also consider questions or suggestions that may lead to a story he can investigate during his remaining days in Iraq, though of course his ability to pursue answers to questions he doesn't already know will understandably be quite limited.

We do not know how much mail this call will generate, so please be patient if it takes Dahr a while to respond or if you do not get a direct, personal response but one appears in public. The situation is extremely tense in Baghdad, as you all know from having read Dahr's weblogs and articles -- right now, that means sending a letter of praise or affirmation might go a long way toward keeping Dahr's spirits up.

We will honor any requests to publish questions anonymously.

The second related item we have coming will be showing up in your email box on Monday. It is a very special message and appeal regarding the case of Sadiq Zoman, the Iraqi family man who was apparently tortured while in US custody and whose story Dahr first covered in January, and then again for TNS last month. Please be sure to pay attention to that message when it arrives -- it's going to contain something rather different than you've seen from us so far.

Third, we are currently building software to host photo galleries on our site. We are honored that the first such gallery will contain some of the incredible photography Dahr has taken over the past 10+ weeks in Iraq. Keep an eye out for that some time this week, if all goes as planned.

June 16, 2004

Beirut, Iraq

Dr. Faiq Amin, the manager of the Medico Legal Institute (ie, the Baghdad morgue), told me a couple of days ago that their maximum holding capacity is 90 bodies.

Since Janurary an average of over 600 bodies each month have been brought there. Of these, at least half have died of gunshots or explosions. He also pointed out that these numbers do not include the heavy fighting areas of Fallujah and Najaf.

In addition, Dr. Amin said, “We deal only with suspicious deaths, not deaths from natural causes.”

The crime rate in Baghdad is out of control. According to Dr. Amin, this current rate of bodies brought to the Baghdad Morgue is 3-4 times greater than it ever was during the regime of Saddam Hussein.

Dr. Amin said that despite the number of bodies being delivered to his morgue on a daily basis, “I am sure that not all of the bodies that should come here do.” He paused before diplomatically explaining, “Because our legal system has some problems right now.”

Before the invasion, there was a coordinated system between Baghdad and the other governorates which allowed his morgue to track deaths throughout the country, but this too has been smashed along with the rest of the infrastructure of his country.

Outside of the morgue today, a man is mourning the loss of his 5 year-old daughter Najala. Mr. Jassim and his family were driving, he tells me, when an American Humvee abruptly pulled in front of their car, causing him to lose control. His car flipped over, and Najala was crushed.

He was frustrated with the fact that he was being forced to wait yet another day to pick up her body.

“Why can’t we take her? They insist on an autopsy, yet she was crushed to her death because we tried to avoid the Americans and our car flipped. So I must wait to bury my daughter.”

Abu Talat and I give him our condolences, and begin to walk away when Mr. Jassim says, “Be careful, don’t die in Iraq!”

Earlier we had visited the Baghdad headquarters of the Iraqi Police for interviews and to obtain handwritten permission to visit a police station from Brigadier General Amer Ali, who is also the Assistant Commander of the Iraqi Police in the capital.

He isn’t happy with the situation in his country. “Now everything is smashed,” he told me. “We are in a crashed country.”

Major Said, the Information Officer for the Baghdad police, was overtly negative about the occupiers of his country. He said: “The Americans invaded our country. They are the invaders, so of course Iraqis don’t like to work with them.”

He addressed the ongoing problem of US soldiers occupying their police stations.

“While the Americans are in our stations, nobody comes to us for help because they are afraid of them,” he said. “This is interfering with our men doing their job, as well as Iraqis getting assistance.”

He was frustrated, and the longer we talked the more it came out, and at one point he was almost ranting.

“We didn’t want this 'democracy' to come. This is not democracy here. Even if I say this as a civilian and not as a police officer, I can say it would be better if the Americans let us do our work and stayed out of our stations. The Americans are making IPs into targets.”

While walking out of his office, since we’d told Major Said we were heading towards Adhamiya for some lunch, he said, “Adhamiya is the next Fallujah.”

Over in Adhamiya we were dining on tasty kebabs on a sidewalk roughly 200 meters from the Adhamiya Palace, which is the US encampment in the heavily pro-resistance area of Baghdad. At 2pm three huge explosions sounded from inside the US base. Mortars, promptly followed by a huge black billowing plume of smoke from the target.

Everyone in the café was watching the smoke and spontaneous celebrations erupted as men clapped, cheered and yelled. “Here they go! The Americans have been killed!”

We continued eating, not missing a beat in our conversation. Abu Talat and I have grown very accustomed to the explosions that rock Baghdad on a regular basis these days. He looked at me and said: “You know, Dahr, I used to read about how the Lebanese got used to the bombs in Beirut. I never thought that could happen to me, yet here I am.”

“I know, and now me too,” I said, and we laughed together at the insanity of what has become our everyday life while working in occupied Baghdad.

We left Adhamiya and traveled to the Asha’ab Iraqi Police station. As I mentioned before, we had obtained written permission from Brigadier General Amer Ali from the Central Command Headquarters of the Iraqi Police in Baghdad. General Ali is also the Assistant Commander of all of the IPs in Baghdad.

So we felt pretty confident about getting into this police station to conduct some more interviews.

At Asha’ab Police Station, US soldiers were scattered across the roof, and a Humvee sat near the entrance at the suicide blockades.

Nevertheless, we wheeled around back and attempted to enter. After all, we were carrying our handwritten permission from the Assistant Commander of the Iraqi Police.

Our entry was denied. Despite seeing our permission letter, an American Military Policeman named Schneider took my passport and disappeared inside for 15 minutes. He returned, handed me my passport after calling in a check to the CPA and told me: “You must contact the Public Affairs Officer at the CPA for information about the Iraqi Police stations. Press aren’t allowed inside.”

So, in sum, a US MP effectively usurped the authority of an Iraqi Police Brigadier General who is the Assistant Commander of all of the police in Baghdad.

So much for sovereignty.

It brought to mind something said by Bassim Mahmoud Hamid, the Iraqi Police spokesman for the Ministry of the Interior, in a recent interview at the CPA:

“We are ready to take over the security situation, because we know how to do this. The Americans will commit the biggest mistake in their life if they don’t let the Iraqis control the security situation.”

June 14, 2004

Hep E on 'Vietnam Street'

I haven’t slept very well the last couple of nights, as the growing anxiety of car bombs has me waking at the smallest noises outside my window nowadays.

Dave was typing on his computer as I walk past him to the kitchen to make some coffee at 8:15 this morning and a huge explosion rumbles down the street near Tharir Square.

“Morning, man,” I said. “Morning,” he replied as we both stare at the huge, brown mushroom cloud that rises above the buildings out our window.

Our daily car bomb viciously welcomed another day of this wretched occupation of Iraq.

At least 13 people died in this one, according to wire reports. The targets were the passengers in several of the typical SUV’s used by CPA contractors. Five of the foreigners are killed, in what was apparently a carefully planned and orchestrated attack.

In the aftermath of blood and chaos, reports said, the front of a nearby building was left sheared and scores of Iraqis began dancing on and around the charred vehicles while holding pieces of twisted metal blown from the vehicles over their heads and chanting, “Down, down America!” and “America is the enemy of God!” Then the vehicles were set abaze.

As the crowd grew in size and furor, US tanks with soldiers in riot gear arrived to seal the area. Soldiers kept their guns aimed at the angry crowd as investigators attempted to collect evidence from the scene of devastation.

I went back to Sadr City to interview doctors at Chuader Hospital. Dr. Qasim al-Nuwesri, the head manager there, said his hospital often receives upwards of 125 dead and wounded Iraqis each time fighting between the Mehdi Army and US soldiers breaks out in the Shi’ite slum, which the US military refers to as the “Black Zone” of Baghdad.

“Whenever large groups like this are brought in, we know it is because of the Americans,” he said in a rare slip of sentiment. For during the rest of the interview he was very careful not to reveal too much about the misdeeds of the occupation forces in his area. He, like so many other doctors and hospital administrators I’ve interviewed over the last 2 months, won’t answer some of my more pointed questions regarding civilian casualties or troops raiding the hospital to interrogate or arrest wounded fighters.

He was quick to point out the struggles his hospital is facing under the occupation. “We are short of every medicine,” he said while insisting that this rarely occurred before the invasion. “It is forbidden, but sometimes we have to reuse IV’s, even the needles. We have no choice.”

This hospital treats an average of 3000 patients each day.

Another major problem that he and other doctors spoke of was their horrendous water problem.

“Of course we have typhoid, cholera, kidney stones... but we now even have the very rare Hepatitis Type-E…and it has become common in our area.”

As a quick google search reveals:

HEV…is transmitted by the fecal-oral route. Transmission is associated primarily with ingestion of feces-contaminated drinking water. The highest rates of symptomatic disease (jaundice) have been in young to middle-aged adults... particularly among pregnant women in the second or third trimester. Fetal loss is common. Case-fatality rates as high as 15%–25% have been reported among pregnant women. Perinatal transmission of HEV has also been reported. Signs and symptoms, if they occur, include fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, abdominal pain, and fever. Hepatitis E has a low (0.5%–4.0%) case-fatality rate in the general population.The best prevention of infection is to avoid potentially contaminated water and food.

Dr. Qasim al-Nuwesri said a German NGO called APN was bringing in water trucks for a while, but they still only had 15% of the necessary clean water supply to operate hygienically.

Upstairs in a room full of 7 younger doctors, we found them even more forthcoming with information.

“The most important thing is no clean water,” said Dr. Ali, a 25 year-old resident physician, while the other six doctors in the room nodded in agreement. “This problem is affecting us so much,” Ali added.

He also said that US soldiers have periodically stormed his hospital looking for wounded resistance fighters. “They come here asking for patients, and are very rough because they shout, cuss, and aim their guns at people,” he said. “We have patients run away when the Americans come, and then we hear that they die at home because they didn’t get their treatment.” According to Dr. Ali, US soldiers also entered the hospital in order to remove posters of Muqtada Al-Sadr from the walls.

Dr. Ali described more of the horrendous conditions the hospital has faced under the occupation like the ongoing power, water, medicine and equipment shortages. Again the other doctors nodded in agreement. “I think the cause of these worse conditions is the Americans,” he said firmly at the end of our interview.

Driving out of the sewage-filled, garbage-strewn streets of Sadr City we passed a wall with “Vietnam Street” spray-painted on it. Just underneath this was written, “We will make your graves in this place...”

Shortly after taking this picture from the car window, we were pulled over by two men in a beat up car who had waved us down. One of them, holding his hand on a pistol beneath his dishdasha, asked what we were doing, who we are, and why we were taking pictures. After our interpreter does a brilliant job of explaining to him that we were writing about the situation of the hospital and are Canadian, the self-proclaimed member of the Mehdi Army begged our pardon. “Excuse us, Sir, but we are defending our city. We are at war with the Americans here, and we are responsible for patrolling this area.”

When we told him we photographed the “Vietnam Street” graffiti, he said, “We call it this because we’ve killed so many Americans on this street.”

He’d wanted to take us to a sheikh to question/interrogate us, but thanks to Hamid being quick on his feet, we avoided the detention and promptly left Sadr City.

Later today, after visiting the Baghdad Morgue (that’s another story for another time), Hamid and I picked up some food and were driving back to the hotel.

We passed yet another group of Humvees and soldiers near a fuel station. As drove by them in the blazing heat, Hamid shook his head. He was pro-invasion, but now does his best to cope while watching what is left of his beloved country disintegrate with each passing day. I tell him I think Iraqis are amazing... for all they have dealt with, and now this, how do they go on?

“Each day we know it is up to God to decide if we will be spared from a bomb. We Iraqis have no choice but to take it day by day,” he calmly explained.

“I understand,” I say while nodding.

Tonight I’ll remember his words when I lay down to sleep, knowing theywill bring me deeper sleep for a change.

NewStandard Article: "Americans, Iraqis Vie for Control of Security Forces"

We've posted another hard news article by Dahr Jamail:

The Iraqi Police and Civil Defense Corps find their work hampered by US

authorities, but signs emerge that greater independence for local security

forces means greater control by the growing resistance...

Dahr travelled all over to get this story. We are going to be hearing more and more in the next few weeks and months about just who controls the Iraqi Police and paramilitaries.

Dahr went back to Fallujah to find out how the Civil Defense Corps, police and mujahideen are getting along now that the Marines have pulled out. And he talked to people from all walks of life, including numerous high-ranking security officials, to figure out what the police are up to and what people think about them. This is not the kind of story just anybody can pull off. Don't miss it...

June 13, 2004

“It has begun.”

Several of us are sitting in the hotel room having lunch, watching the news trying to keep up with the violence daily engulfing Iraq. Let me give you a quick rundown from the last 24 hours.

Late last night fighting continued in Sadr City between the Mehdi Army and occupation forces... leaving at least five Iraqis dead, three of them civilians.

This morning the Republican Palace, where Bremer is headquartered, was blasted by a rocket.

Shortly after 9 this morning, a huge blast rocked Baghdad when a car bomb detonated near Camp Cuervo, a US Army Camp in the northern part of the capital. The explosion left 12 Iraqis dead, 4 of whom were policemen.

Another car bomb exploded this evening north of Baghdad in an attack on US troops-killing one soldier and wounding 2.

According to the Washington Post, there have been 16 car bombs this month thus far, and today is June 13th.

Assassinations of government officials continue unabated. Last night in Baquba, an attempt on Majeed Almani Mahal, a senior Iraqi Police official, left him wounded in a local hospital.

Also yesterday, the chief of the border police in Iraq, Major General Hussein Mustafa Abdul-Kareem was wounded when assassins attacked his convoy in Baghdad.

The attempts grew more lethal yesterday when the Iraqi deputy foreign minister, Bassam Kubba was shot dead while driving to work.

Today Kamal al-Jarah, an official from the Education Ministry, was assassinated near his home.

While we were watching all of this news, small, black helicopters of special operations forces and private security contractors buzzed like flies over central Baghdad and sirens blared randomly from the blazingly hot streets.

As footage of cars with broken glass and bullet holes in their frames flashed across the screen of the television, my friend’s translator, Hamid, an older man who has grown weary of the violence, said softly: “It has begun. These are only the start, and they will not stop. Even after June 30th.”

And the news of more assassinations continues to roll in. Last night Iyad Khorshid, a popular Kurdish cleric in Kirkuk, was killed in the city where tensions between the ethnic groups is rising each day.

All of this atop the ongoing killings of the intelligentsia in Baghdad, where over the last year of occupation there have been a monthly average of 10-15 assassination attempts on Iraqi professors, scientists and academics, about 5 of them successful each month.

Yet another example of this occurred today at Baghdad University, where a geography professor, Sabri al-Bayati, was executed in the streets.

Of course, foreign contractors can’t be left out of the slaughter. On this front, today we got the news that the brutally butchered body of a Lebanese construction worker was found yesterday near Fallujah. He had previously been kidnapped.

Nor can we forget about the journalists -- two Iraqis working for the US-controlled Al-Iraqia TV station were found dead near the border of Syria. Apparently they were killed yesterday.

Lakhdar Brahimi announced his resignation yesterday from his position of the UN envoy to Iraq due to what he described as great difficulties and frustration from his assignment.

Not long ago Brahimi said: “Bremer is the dictator of Iraq. He has the money. He has the signature. Nothing happens without his agreement in this country.”

Presenting what was apparently the US idea of a solution, Brigadier General Mark Kimmitt said of the military plans in Iraq after the “handover” on June 30th; “We will not be pulling out of the cities. We will not be relocating.”

“The student is gone; the master has arrived.”

This became a very popular saying in Iraq after the US ousted Saddam Hussein.

The situation continues to degrade in occupied Iraq. I know I’m beginning to sound like a broken record... but the need to describe life on the ground here continues, as I see it slipping from the news as of late. Overshadowed by more dramatic stories like car bombs and heavy fighting, the silent suffering that has become the daily reality here just isn’t catching much attention.

One exception was the LA Times recently reporting the US military's claim that in the last 9 weeks over 800 people in Sadr City have been killed by occupation forces. Doctors I talked to in the main hospital there confirmed this, adding that the vast majority of them were women and children.

Salam, one of my Iraqi friends, asks: “Why is the news so quiet about all of these things? In the last 6 months 20 people I know have been killed, for nothing! They weren’t fighters -- they were just living their life.”

This is life in Iraq today.

I’m trying to pay closer attention to these daily occurrences, as I too have become desensitized by the bombs as I’ve grown more accustomed to this horrible situation. So I’ll try to point out more of what I’ve noticed as of late.

It isn’t the huge bombs -- the ones make the news, horrendous as they are -- that have the greatest impact on Iraqis. It is the ongoing, daily suffering of the Iraqi people. People dying from bad water and starving to death because there aren’t enough jobs just don’t grab the attention that bombs demand from the media.

And other things... last week Salam was in a car accident, and called to tell me he was injured. Since it was at night, knowing it was unsafe for me to leave the hotel he asked me to call a friend to come help him. Thankfully, Abu Talat was home and quickly drove to his aid. This is the 9-1-1 service in Iraq. Without much infrastructure to speak of, Iraqis have come to rely more and more on their friends, families, tribes, and mosques.

Then there are the constant reminders to Iraqis of how little control they have over their lives.

Driving across the double bridge (formerly Saddam Bridge) in south Baghdad there are huge, black metal sheets along one side of the top of it. On each of them is written:

By Order Of The Coalition Forces

Do Not Tamper With Or

Remove Metal Sheets

Under Penalty Of Force

I was with my friends Hamoudi and Samer as we traveled to see some other friends for a visit and lunch. I asked Hamoudi how he was doing.

“This is like a bad dream, man. I need to get out of here for a break.”

For Iraqis, this is far easier said than done.

While at our friends', the laughing and joking is inevitably broken up by someone crying about the unbearable situation in their country.

At the same time, of course, the more visible violence continues. Yesterday morning there was more fighting in Najaf. In the last week alone four Iraqi Police stations have been blown up. There has been fighting on the outskirts of Fallujah, several bombs in Al-Adhamiya yesterday, IED’s detonating under US patrols, political assassinations in Kirkuk, nearly daily fighting in Sadr City, and the assassination today of Bassan Kubba, the Undersecretary for Multinational Affairs and International Organizations.

I recently interviewed another detainee from Abu Ghraib. Some of what she told me reminded me of a quote from George Bush at the 2003 RNC Gala.

“Iraq is free of rape rooms and torture chambers.”

Um Taha was detained for 4 months. She told me that while in Abu Ghraib she knew that many of the women in the prison were being raped.

She told of detainees who would hold their Qu’ran out of their cell bars in order to have some light to read with. “And when they did this,” she said, “soldiers would hit them on their arms.”

Um Taha added that soldiers were distributing Christian Bibles in Arabic to the teenage detainees, and that soldiers were forcing detainees to speak English to them.

She told of being forced to use a sieve to separate feces from urine in a waste bucket from the latrine in Tikrit where she was held prior to her transfer to Abu Ghraib. Once this job was done, a soldier dumped gas on the feces, lit them, and made her stir them for half an hour.

During November, while in Abu Ghraib, she said many of the detainees rioted against their mistreatment. She stated that as a result, 14 Iraqi men were stripped naked and sacks were placed over their heads by U.S. soldiers, and brought into the corridor beneath her cell. Thus, she had a clear view of the atrocities which ensued.

“The soldiers made them all stand on one leg,” Um Taha recounted. “Then they kicked them to make them fall to the ground.”

She said that Lynddie England, the female American soldier made infamous in the widespread incriminating photos, was dancing around laughing while using a rubber glove to snap the detainees on their genitals. “The soldiers also made all the men lay on the ground face down, spread their legs, then men and women soldiers alike kicked the detainees between their legs,” Um Taha said quietly.

After pausing, she added, “I can still remember their screaming.”

She said that in addition to this, the detainees were ordered to crawl around the corridor on all fours and make cow and sheep noises as the American soldiers laughed at them.

On September 11, 2001, George Bush said, “I don’t care what the international lawyers say, we are going to kick some ass.”

June 08, 2004

Smashed Windows, Intricate Webs

While a restful experience, driving around the mountains and green fields of Kurdistan did not provide the complete escape from the troubles of Iraq for which we had hoped.

The cousin of a friend manages a hotel in Erbil... one of the nicer lodges in the city. While dining with him in the empty restaurant he explained that there are no guests due to the fact that the private security company Dyncorp has been renting the entire place since January... so aside from when their personnel stay in the 60-room hotel, it sits empty. They stay at the hotel while training new Iraqi Police, among other things, and he told us they’ve signed a two year contract.

Each day of the four spent in the north I’d seen the armored GMC’s with the huge antennae used by these private security groups and the Secret Service racing along the roads from time to time, their tinted windows reflecting the beautiful countryside.

There are, of course, loads of Peshmerga checkpoints -- since we hailed from Baghdad with an Arab driver, we were searched at most of them.

Nevertheless, the reprieve from Baghdad was long overdue. In Shaqlawa, a beautiful little town on the slopes of a large ridge, we dined in the garden of a small farm amidst cooler temperatures. Earlier that same day we’d cooled our feet in the water of a mountain spring while birds chirped. Periodic views of snow-capped peaks in the distance had me longing for home; from time to time I even forgot about things like Abu Ghraib, military patrols in cities and the electricity shortage in Baghdad.

The opinions of the few Kurds I spoke with ranged across the board -- those who are doing better financially tended to favor the occupation, while others who appeared to be suffering more were against it. A few refused to talk politics altogether.

Life in a war-torn country is never simple. Yesterday we drove to Sulemaniyah, a sprawling city surrounded by rolling mountain ridges. After finding a hotel, Abu Talat had parked his car amongst several others on a small street. We’d checked in, had some chai and were venturing out to find an internet café when he noticed his car was not where he’d left it.

A traffic policeman told him it had been towed. Hoping to just go pick up the car he hailed a taxi and was off. Upon arriving at the impound, he found the car smashed up, along with a few other cars with Baghdad license plates. He was taken inside a house and interrogated by a Peshmerga officer, who asked him many questions such as: What are you doing here? What is your tribe? Why did you come to Kurdistan? When are you leaving?

After he was released, he found his car -- the trunk smashed in and lock broken, driver's side window smashed in, fuel line cut, battery cables cut, back seats torn out and the antennae broken off. Apparently several Peshmerga, fearing another bombing like that last winter in Kurdistan which killed so many people in a mosque, were trying to prevent another attack.

The next day, after having parked the car in a garage, when Abu Talat went to pick it up he asked the watchman why his mouth was bloodied and swollen. The man told him that late last night five drunk Peshmerga had come demanding money, and when he wouldn’t give it to them they pistol-whipped him.

A local Kurdish man at the hotel, upon hearing this story, said it is business as usual in Sulemaniyah... that the Peshmerga are acting like the thugs of the mob boss Talabani.

So even up in restful Kurdistan the symptoms of war and unrest remain. One must be patient at the checkpoints and be wary of where one parks the car.

We stop for lunch at a friends place in Kirkuk. An older Turkman spoke of the growing rift between the Kurds and Turkmen in the city. He told of how the Arabs and Turkmen in Kirkuk are banding together against the Kurds there. I asked him what the solution is, and he felt it was to go by the ’57 Census in the city, where Turkmen were the majority. So, again I ask, what is the solution? Each of the last few times I’ve been through Kirkuk the topic of the Turkmen vs. Kurds is the first thing that comes up. It is tense there, and seems to be getting worse with time.

After a good meal and chai we continued our dry, windy journey, still missing a window. Exiting Kirkuk we passed the old Saddam portraits which have been blasted into rubble.

The occupation forces, having removed the regime of Saddam Hussein, now face the challenge of sorting out the complex web of ethnic groups and tribes in the north; a challenge that Hussein never could effectively manage. One way or another, at some point, this situation will have to be resolved by the occupiers.

The normalcy of rural Iraq -- the green crops lined with date trees, tan homes blending into the desert sands, and intermittent chai stands along the road we take -- begrudgingly give way to occupied Baghdad. As summer temperatures continue to rise, the setting sun bathes the destruction of bombed out buildings, Dyncorp men aiming their guns at us as we pass their white SUV’s, long petrol lines, and polluted air a beautiful yet angry orange.

June 03, 2004

“Why are they doing this to us?”

He is a well spoken, handsome lawyer, just a year older than I am. He worked as a diplomat who coordinated NGOs and foreign governments in order to bring aid to his country during the sanctions.

He was detained and accused of being a spy for Saddam Hussein, even though he is not even a Baathist.

He was hung from his ankles for hours in Abu Ghraib, until he passed out.

I ask him what else happened to him in there. He pulls up the legs of his trousers to show me two electrical burns on the inside of his knees, and points to two more on his elbows.

We all know the usual parts of this story: his head was bagged and hands and ankles tied too tightly, roughly thrown in an armored vehicle and driven to Baghdad Airport prison. Then to Abu Ghraib for 2 months, then to a prison in Basra, then back to Abu Ghraib for seven months.

At the Airport prison (which Iraqis refer to as Guantanamo Airport) he was interrogated five times, then ten more times at Abu Ghraib. At each place he was beaten until he passed out, forced to beat other detainees, deprived of food and water (he lost 25 kilos while in detention), offered no medical care, received threats on his life, was threatened that his wife would brought in and raped in front of him, had rats and cockroaches as cellmates. He was kept in a cell 2 meters by 1.5 meters.

Or maybe you haven’t heard all of this already...

Maybe you didn’t hear that the lead CIA man who tortured him referred to himself as “Satan.” Or that while he was praying and reading his Koran female soldiers came in and flashed their breasts at him, then sexually humiliated and abused him.

What else is news? That there were 16 showers for 650 detainees. That there was no medical treatment, except for 30 out of 650 detainees -- who were given aspirin for infections and viruses. That when he was finally allowed to use the toilet after being forced to wait for hours, soldiers would open the door on him.

Of course there is more. There is much, much more. But I’ll save that for later, because it isn’t easy to type when ones hands are shaking.

Since he has been out he has not slept much, and has nightmares when he does manage to catch fleeting moments of shuteye.

His home was destroyed while he was in detention.

Then there is his aunt. I interviewed her tonight as well. A kind, 55 year-old woman who used to work as an English teacher. She was detained for four months, in as many prisons: Samarra, Tikrit, one in Baghdad and of course, Abu Ghraib. She was never allowed to sleep through a night, she was interrogated, not given enough food or water, no access to a lawyer or her family. She was abused verbally and psychologically.

But that isn’t the worst part. Her 70 year-old husband was detained and beaten to death. But that took 7 months.

She’s crying as she speaks of him... as are Abu Talat (my translator) and I.

“I miss my husband,” she says, standing up and addressing the room. “I miss him so much.”

She shakes her hands as if to fling water off of them... then holds her chest and cries some more.

“Why are they doing this to us?” She doesn’t understand what is happening. Two of her sons were also detained, her family completely shattered. “We didn’t do anything wrong,” she sobs.

After a short time we walk out towards the car to leave... it is already too late to be out -- well past 10 p.m. She asks us to please stay for dinner, in the midst of thanking me for my time, for listening, for writing about it all.

I am speechless.

“No, thank you, we must get home now,” says Abu Talat. We are all crying.

No words in the car as we drive toward the full moon. Finally, Abu Talat asks me, “Can you say any words? Do you have any words?”

“No,” I mumble. “No...”

Violence in Baghdad, Wordplay in Fallujah

A rumbling explosion just let off near my hotel. This not too long after getting back from Adhamiya where I was talking to witnesses at the scene of yet another car bomb; the third in as many days here in Baghdad.

At the scene in Adhamiya the scorched, crumpled shell of the car was pushed off to the side of the road. A brick wall nearby bore pockmark scars from the shrapnel. Store windows 50 meters away were shattered. I passed a dried pool of blood on the sidewalk near the small bomb crater while walking slowly to a nearby shop where I met Abdel Halik Al-Samarri, a real estate broker who witnessed the attack.

“Two armored vehicles passed up and down the street four times, then two Land Cruisers of the Americans passed by the parked car,” said Abdel, still shaky hours after the bombing. “Just as they passed the car it exploded.”

Ismail Obeidy, a lawyer who works at the real estate office with Abdel, ran towards the burning car to assist a woman who had had pieces of shrapnel lodged in her legs. “I carried her across the street, and put her in a car which took her to the hospital,” he said. Just three minutes after the first blast as scores of people had congregated around the burning car to survey the damage, a second, much larger explosion erupted which killed several people and injured many more.

“If the Americans will stop invading our streets, no explosions will happen,” cried Ismail in frustration and anger. He went on to say that a small crowd gathered and began yelling anti-American slogans at US troops when they cordoned off the area.

Car bombs are becoming a daily occurrence in Baghdad, and there is nothing the locals can do about it.